Net-Zero: The Promise, the Problem, and Why it Matters Now

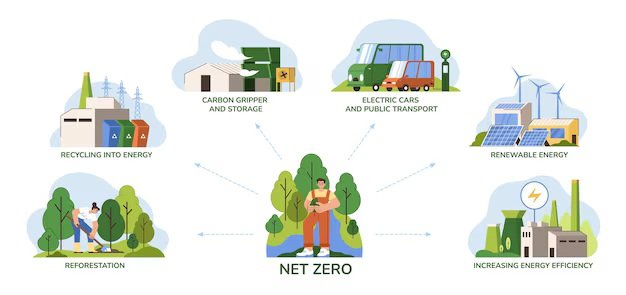

Net zero has become the headline goal shaping the agendas of governments, companies, and cities worldwide. It means cutting greenhouse gas emissions as much as possible and then balancing the remaining emissions by removing carbon from the atmosphere. The idea is that if we can reach that balance, we stand a chance of keeping global warming close to 1.5°C.

The vision is to achieve cleaner air in our cities, more affordable energy over the long run, and economies better prepared for future shocks. But the gap between what’s promised and what’s delivered is still wide. Many corporate strategies rely heavily on future carbon removals or offsets rather than addressing emissions directly today. Meanwhile, several countries continue to invest in new fossil fuel projects while talking up their long-term neutrality goals.

The International Energy Agency’s original Net Zero by 2050 roadmap reminds us of what’s actually needed: hundreds of near-term actions, from rapidly scaling up clean electricity and energy efficiency to making deep, immediate cuts in fossil fuel use. Only with this kind of momentum can we keep the 1.5°C target within reach.

Net-zero, therefore, means two simultaneous things: act now to cut emissions, and build credible, regulated ways to measure and — only where truly necessary — remove what remains. But the evidence from recent studies is worrying. Large surveys and transition assessments show that most listed companies have not yet reallocated capital away from high-carbon assets or disclosed credible, finance-aligned transition plans. A report by the Transition Pathway Initiative in 2025 found only a small improvement year-on-year in credible disclosures and warned that many firms still rely on offsets rather than operational decarbonisation.

People and Projects: Real Progress on the Ground

Net-zero isn’t just headline targets—people and communities are already making it real in practical ways. In Oxfordshire, a kitchen-table idea grew into the Low Carbon Hub, which now runs dozens of community-owned renewable projects and returns profits to local insulation and energy-saving work. “The ambition was really that we just believed a better energy system is possible, one that’s not powered by fossil fuels, and one that benefits local people,” the group’s communications lead told The Guardian. That story is not glamorous, but it is tangible: community hydro and a large community solar park now supply local energy and fund local carbon cuts.

At a different scale, new carbon-removal technology is being trialled. Climeworks opened the Mammoth direct-air-capture (DAC) plant in Iceland to pull CO₂ straight from the air, using geothermal power for energy. The company frames DAC as part of a broader solution: removal complements deep cuts, it does not replace them. But DAC today is expensive and early-stage — the plants are important proof points, but not a silver bullet. “Starting operations of our Mammoth plant is another proof point in Climeworks’ scale-up journey,” a company co-founder told Reuters in 2024.

Those two examples illustrate a central truth: progress to net-zero will be a patchwork of bottom-up community projects, nation-scale policy, and — where necessary and verifiable — engineered removals. Each piece can work only if the others do too.

What the Research Shows (and Why Many Pledges Fall Short)

The science and watchdog reports are blunt: many net-zero pledges lack the credibility necessary to ensure real climate outcomes. Independent trackers and academic studies show a pattern: pledges proliferate, but many lack aligned finance, clear near-term targets, or transparent reporting.

But the gap between what’s promised and what’s delivered is still wide. Many corporate strategies rely heavily on future carbon removals or offsets rather than addressing emissions directly today. Independent assessments back this up: the Transition Pathway Initiative’s 2025 State of Transition report found that while more companies are disclosing their reliance on offsets, very few are actually shifting capital spending away from carbon-intensive assets. In fact, nearly all of the companies assessed had not aligned their investment plans with decarbonisation. The report also warned that offsets are often presented as the primary path to net zero rather than the last resort they are meant to be.

Academic work also reflects this concern. Analyses published in Nature Climate Change show that many corporate targets either expire, disappear, or are not followed by measurable action — a pattern that weakens accountability and invites legal and investor scrutiny. The study tracking earlier corporate targets found that a significant share either failed or vanished at their end date, highlighting the lack of robust accountability mechanisms.

At the national scale, the picture is mixed. The IEA’s roadmap — still a central technical reference — stresses that electricity must be largely decarbonised, that transport and industry must electrify or switch to low-carbon fuels, and that removal technologies will be needed for some residual emissions. But the IEA also cautions that its pathway assumes major near-term action; delays or reliance on speculative technology will make 1.5°C impossible. The agency further suggests that the global energy sector must follow a detailed set of milestones that leave little room for backsliding.

Additional real-world signals complicate the story. Investigations and reporting have documented instances where energy companies expanded fossil exploration even while promoting net-zero rhetoric; critics call that inconsistency a form of greenwashing. The Guardian reported in 2024 that major oil and gas players have increased exploration spending despite making long-term net-zero claims, a move that raises questions about whether corporate pledges match operational priorities.

A short data snapshot (compiled from recent reports and studies cited throughout this article)

| Indicator | Recent figure (source, year) |

|---|---|

| Companies disclosing no plan to shift capital from high-carbon assets | 98% (LSE/TPI-related review, 2025). |

| Portion of companies satisfying meaningful disclosure thresholds (MQ20) | ~9% (Transition Pathway Initiative, 2025). |

| Current scale of commercial DAC removal (approx.) | ~10,000 tonnes/year globally (Climeworks and peers, 2024). |

| Community energy groups active in the UK | ~600 groups (Low Carbon Hub reporting/Guardian, 2024). |

These figures show two things: that systemic change remains incomplete at corporate and national scales, and that bottom-up projects can and do deliver measurable emissions reductions — but they need supportive policy, finance and markets to scale.

Practical Steps That Work — and What Readers Can Do Now

Net-zero becomes credible when short-term action and long-term planning are locked together into rules, finance and measurable outcomes. Experts and practitioners point to a few consistent lessons.

First, require near-term, verifiable cuts. Targets that stop at “net-zero by 2050” without milestone years and sectoral pathways allow delay. The IEA and other technical bodies recommend binding near-term milestones — for example, per cent reductions by 2030 in power, transport and industry — not just distant goals. Those near-term milestones are essential to keeping 1.5°C within reach.

Second, align finance with climate goals. Investors and regulators need to see capital expenditure redirected away from high-carbon assets. Recent reviews by transition analysts show little large-scale shifting of investment plans across most sectors. Fixing this requires clearer rules, mandatory transition plans, and stronger investor pressure. The 2025 briefing by the Transition Pathway Initiative found that disclosures improved slightly, but capital-allocation alignment remains rare.

Third, separate removals from reductions in accounting and policy. Removal technologies have an important but limited role; they should not be used as a substitute for emissions cuts. Where removals are used, they must be counted transparently and credited only when permanent and additional. Reporting frameworks and regulation should make that separation explicit — a point repeatedly raised by carbon-removal practitioners and scientists. Reuters and FastCompany coverage of DAC firms highlights both their potential and the need for cautious, evidence-based policy.

Fourth, fund and scale community action. Local projects — from community solar parks to hydro and building retrofit programmes — deliver real carbon cuts and social benefit. The Low Carbon Hub in Oxfordshire shows how community ownership can lock value and local reinvestment into the transition; supporting many such projects could build public trust and deliver distributed decarbonisation.

Finally, what can readers and local leaders do this week? Demand clarity: ask employers, local councils and financial institutions whether their net-zero claims include clear 5- and 10-year targets and whether they plan to shift capital away from carbon-intensive assets. Support proven local projects — community energy groups, building retrofit funds and public transport improvements — and insist removal credits be used only after deep, verifiable emissions cuts. Investors and citizens alike have leverage: transparency, persistent questions, and local action add up.

Conclusion

Net-zero is not a slogan; it is an operational challenge. The evidence is clear that technical pathways exist, that community projects are already delivering real cuts, and that the weakest link today is credible governance — the concrete, enforceable rules that turn pledges into practice. Policy makers, investors and citizens must act in concert: enforce near-term milestones, align capital, keep removals honest, and scale community solutions. Do that and net-zero can be more than a promise — it can be the plan that protects livelihoods and keeps warming as close to 1.5°C as possible. For the technical roadmaps and data behind these claims, see the IEA net-zero work, transition-pathway reviews and recent reporting on community energy and carbon removal