If you’ve ever watched a tiny black spider in your home turn its big eyes toward you and seem to “look back,” you’ve probably met a jumping spider. For many people, they are the perfect “first spider” — small, curious, and oddly charismatic. For others, they are a source of understandable worry: do they bite? Are they poisonous? Are they good pets? In this piece, I’ve gathered insights from scientific research, hobbyist discussions on public forums, and medical case reports so you can decide for yourself. Researchers now understand jumping spiders’ vision and behaviour better than ever — their eyes give them a narrow, highly detailed colour view that they use to hunt, court, and investigate the world.

In This Article

- Why People Are Falling for Jumping Spiders

- What Science and Experts Say

- Keeping a Jumping Spider: Real Stories and Practical Advice

- Conclusion — Actionable Advice

Why People Are Falling for Jumping Spiders

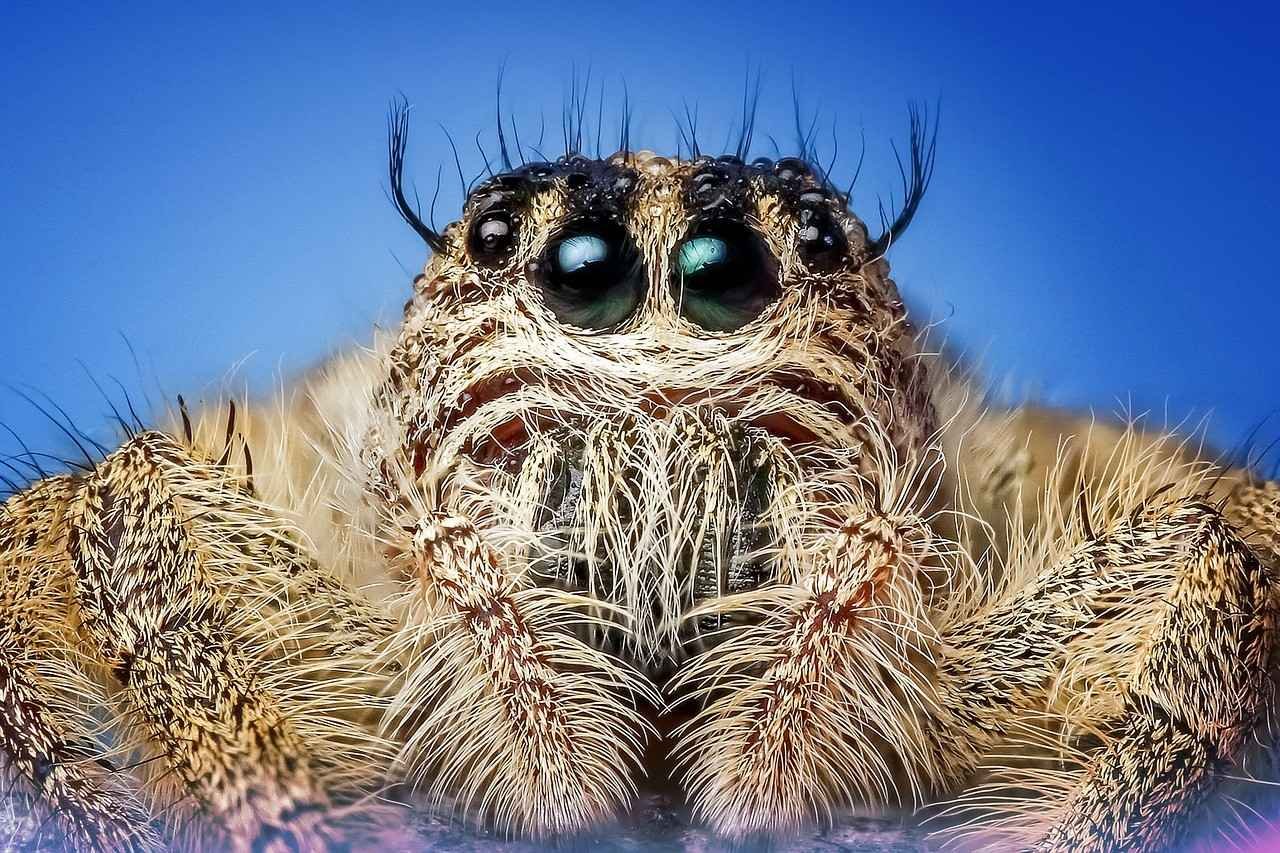

Jumping spiders (family Salticidae) are tiny predators that don’t build webs to catch food. They stalk and pounce, using amazing eyesight and surprising athleticism. Their forward-facing principal eyes provide a crisp, colourful “spotlight” while secondary eyes watch motion all around them. That sensory mix is what makes many keepers describe them as interactive in a way that common pet insects aren’t. “They’ll follow movement, cock their head, and sometimes perform little display behaviours,” a University of Canterbury researcher told Science News in 2021 about these very human-like reactions. This is why a growing number of hobbyists keep them in small, simple enclosures rather than letting them roam the house.

Part of the appeal is low cost and low space. Many keepers in public forums report housing a single Phidippus (the bold jumper) or Menemerus in a jar or small critter-cage no larger than a grapefruit. On Arachnoboards, an experienced hobbyist wrote that a 4×4×7-inch container with ventilation, a few twigs, and a refuge is enough for larger Phidippus species, and that these spiders are “hard as nails” if properly fed and misted. These are real-world accounts from people who keep these animals daily and see them behave in ways that surprise even seasoned insect-keepers.

For many owners, the emotional payoff is immediate. Unlike a fish or a hamster, a jumping spider reacts to you — it notices your movement and often appears to “watch” you. Online, owners post short video clips of their spiders turning toward the camera, stalking a cricket, or displaying male courtship dances. These are not fictional stories — they are the lived experiences of people who share clear photos and descriptions on platforms like Reddit and Arachnoboards. If you want a low-maintenance animal that still feels alive and curious, many say a jumping spider fits the bill.

What Science and Experts Say

Let’s talk safety: jumping spiders do have venom — they are predators — but for almost everyone, that venom is harmless. Medical and science sources repeatedly find that bites are rare and typically cause minor, short-lived symptoms like localised pain, redness, or swelling. WebMD’s overview of jumping spiders emphasises that they are not dangerous to humans and usually do not bite unless provoked or handled improperly. Most bite reports describe mild reactions that resolve in days. At the same time, rare cases exist where a bite led to stronger local effects; an identified case in the New Zealand Medical Journal describes a man bitten by a local Trite species, reporting a stinging pain and temporary symptoms. So the broad scientific picture: mostly harmless, occasionally uncomfortable, and very rarely medically significant.

Why are most bites mild? Jumping spiders are small: many common species are under 15 mm in body length, and their fangs are tiny. Their venom evolved to subdue prey — insects and other arthropods — not to hurt a creature as large as a human. University and field researchers (including well-known jumping-spider experts) emphasise that the spiders’ sensory systems and behaviour make them likely to flee or freeze rather than bite when they encounter something far larger than themselves. Robert R. Jackson and colleagues, prominent figures in Salticidae research, have documented the intelligent hunting and defensive behaviours of Portia and related genera; these studies give context for why jumping spiders rarely deliver serious bites.

Jumping spiders also play an important ecological role. Species like Phidippus audax are predators of crop pests and commonly live near human habitations; extension services note they are among the most common spiders around homes and fields. If you keep one as a pet, you’re engaging with a creature that is both a skilled predator and, in most places, plentiful in the wild. Still, experts warn against indiscriminate wild-collecting: local regulations and conservation ethics matter, and captive-bred sources are often the best option for hobbyists who want to avoid impacting wild populations.

Below is a quick look at a few species people commonly keep, with basic stats compiled from field guides and university sources:

| Species | Typical adult size (mm) | Typical lifespan (yrs) | Common pet-suitability note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phidippus audax (Bold jumper) | 6–15 mm. | ~1–2 years (often ~1 year wild). | Bold, interactive, popular with beginners. |

| Portia fimbriata (Fringed Portia) | 5–10 mm. | ~1–2 years. | Highly intelligent hunter; best for experienced keepers. |

| Menemerus bivittatus (Gray wall jumper) | ~9 mm. | ~1 year (up to 2 in captivity). | Tolerant, common on buildings; good beginner species. |

(Each row above is drawn from species accounts and care guides)

Keeping a Jumping Spider: Real Stories and Practical Advice

If you’re reading this because you’re thinking of keeping a jumping spider, here’s the real-world, practical side based on hobbyist accounts and extension-level care guidance. Start with a single spider and learn its temperament. Many keepers buy or collect juvenile Phidippus or Menemerus species because they are hardy and tolerant of small enclosures.

Fans on Reddit and Arachnoboards consistently share the same basics: provide a vertically oriented enclosure with good ventilation, a small hide (such as a rolled piece of bark or paper), one or two twigs for jumping, and light misting a few times a week so the spider can drink droplets rather than risk drowning in a dish. Feed small live prey — pinhead crickets, fruit flies, or gnats — a few times per week, depending on the spider’s size and activity level.

These are community-vetted practices, gathered from people who have kept these spiders for years and exchanged troubleshooting tips in public threads.

Handling: Most keepers advise against frequent handling. Jumping spiders don’t enjoy being petted like a cat, and an accidental fall can be fatal. A cautious owner describes coaxing a spider onto a cup and carrying it gently rather than letting it crawl on bare hands. If you do allow interaction, pick low and soft environments and watch for warning signals: rapid rearing, raised front legs, or sudden lunges. These are signs the spider is stressed and likely to bite defensively; a tiny pinch is typically the worst outcome, but people with severe allergies should avoid handling altogether. For medical concerns, follow standard first-aid: wash the area, apply a cold compress, and seek medical care if symptoms worsen — the same approach clinicians recommend for most non-dangerous arthropod bites.

Living examples: Across public forums, there are repeatable success stories. One keeper reported that a female Phidippus lived for about 18 months in a small glass jar with regular feedings and occasional misting; the spider moulted several times and laid one egg sac. Another user shared that a Menemerus kept on a sunny windowsill chased and captured flies three times its size with apparent ease. These examples show that, with simple husbandry and respect for species differences, you can keep a jumping spider successfully.

Finally, think about where you source your spider. Some websites sell captive-bred jumpers, while others collect them from their gardens. If you take one from the wild, check your local wildlife regulations — in some regions, removing native invertebrates is regulated, and in others, it is discouraged for conservation reasons. Where possible, consider captive-bred specimens; they are usually acclimated to human care and help reduce pressure on local populations. Extension literature and university web pages about common local species are a good starting point if you’re unsure which species are abundant or protected in your area.

Conclusion — Actionable Advice

If you’re curious and want to try keeping one, start small and safe. Choose a hardy species that’s recommended for beginners (Phidippus or Menemerus are both common choices), buy from a reputable breeder or collect only where legal and ethical, and set up a vertical ventilated enclosure with a hide, perching spots, and a shallow water source via misting. Feed live prey appropriate to the spider’s size twice a week, keep temperature and humidity in normal household ranges, and avoid excessive handling. For children, supervise any interaction and consider observing rather than handling.

If you worry about bites or allergies, remember the science: bites are rare and usually mild, but a small number of documented cases show stronger local reactions, so be cautious if you have a known insect allergy. If you are bitten and have severe symptoms (widespread swelling, breathing trouble, or systemic reactions), seek medical care immediately. For ordinary mild bites, cleaning and cold compresses suffice. According to WebMD, jumping spiders are not dangerous to humans in general; serious outcomes are exceptional and rare.

Jumping spiders are a living reminder that the small creatures in our homes have rich inner lives we are only just starting to understand. They aren’t “pets” in the traditional sense for everyone, but for people who want a low-footprint animal that still surprises and delights, they can be a perfect tiny companion. And if you ever want to learn more — species-by-species notes, enclosure photos, or sources for captive-bred spiders — I can pull more specific care sheets and supplier lists for your country. Would you like help finding a local breeder or a step-by-step care checklist tailored to your first species?

Sources and where to read more:

- Science News, Betsy Mason, “How jumping spiders’ senses capture a world beyond our perception,” 2021. (vision, expert quotes).

- Penn State Extension, “Bold Jumper Spider (Phidippus audax),” 2022 (species notes and commonality).

- WebMD, “Jumping Spiders: Facts & Safety,” 2024 (human safety summary).

- New Zealand Medical Journal case report on a Salticidae bite, 2010s (documented bite case).

- Arachnoboards & Reddit hobbyist threads (keeper experiences, enclosure tips).

- Animal Diversity Web and species accounts for Phidippus audax and Portia fimbriata (size, natural history).

- Bold Jumping Spider (Phidippus audax). (n.d.). iNaturalist.