Community Seagrass Network Launched to Map Coastal Carbon Sinks

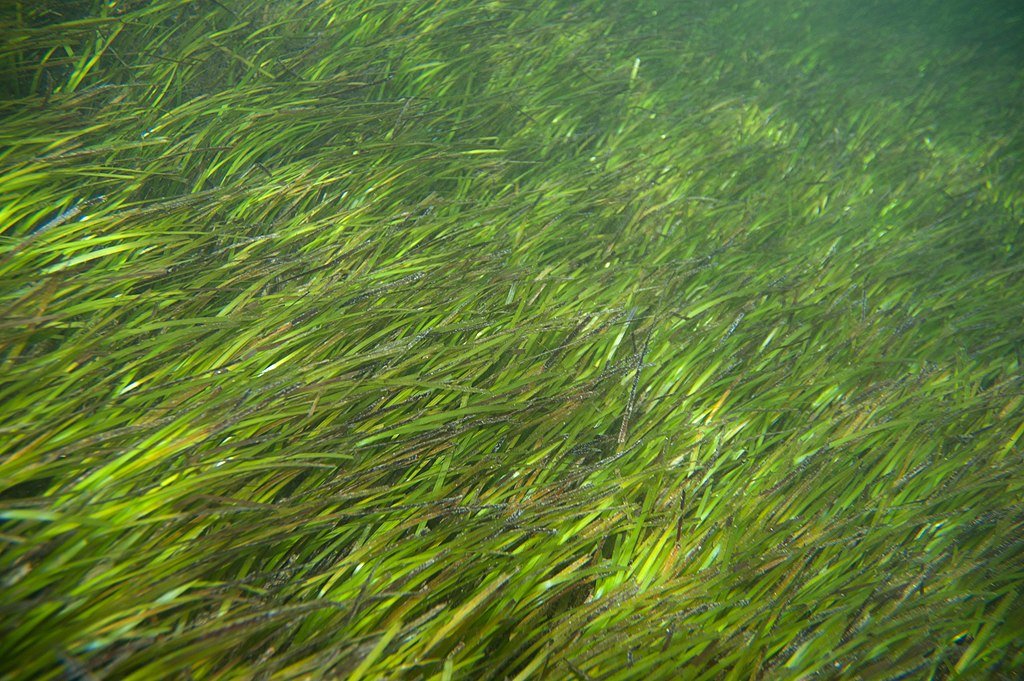

A new wave of community-led mapping projects is bringing the world’s underwater grasslands into sharper focus — and into climate policy conversations. In the last year, scientists, NGOs and volunteer groups have launched coordinated efforts to locate, map and measure seagrass meadows so their carbon-storage value can be counted, protected and, where possible, restored. The work is part science, part community action: teams are combining satellite images, field surveys and crowdsourced photos to produce maps that can be used by fishers, planners and national governments. According to Project Seagrass, a fresh global analysis shows many seagrass meadows are under threat, even inside protected areas, prompting calls for better mapping and monitoring.

Mapping matters because you can’t manage what you don’t know exists. Local volunteers snapping photos from boats or snorkels are now part of the same data stream used by university researchers and national agencies, and that creates a fast, low-cost route to robust maps that can feed into blue-carbon accounting and coastal planning. This article explains why those maps are urgent, how community networks are doing the work, and what governments and coastal communities can realistically do next.

In This Article

- Why Seagrass Mapping Matters for Climate and Communities

- How Communities and Science are Mapping Seagrass

- From Maps to Action: Policy, Restoration and Practical Steps

- Conclusion

Why Seagrass Mapping Matters for Climate and Communities

Seagrasses are among the planet’s most efficient natural carbon sinks. They capture carbon from the water and atmosphere and bury a large share of it in sediments below the plants — a form of storage often described as “blue carbon.” A recent peer-reviewed analysis estimated that seagrass carbon stocks at risk of degradation could release about 1,154 teragrams (Tg) of CO₂ if lost, with an estimated social cost in the hundreds of billions of dollars — a stark number that underlines the climate risk of ignoring these habitats. According to the study, protecting seagrass is therefore a climate-relevant conservation priority.

The broader value of seagrass goes beyond carbon. Seagrass meadows improve water quality, shelter juvenile fish, help prevent coastal erosion and support tourism and fisheries that local people rely on. A regional study that supported national mapping in Seychelles found seagrass areas measured in the tens to hundreds of thousands of hectares and emphasized how mapping is an essential first step to including blue-carbon sinks in national greenhouse-gas inventories. A report by Seychelles’ MACCE in 2025 found that mapping enabled the country to begin estimating carbon stocks and plan protection measures.

At the same time, global assessments show we simply don’t have a complete map. Citizen science platforms and national projects are filling big gaps, and producing evidence that many meadows are nearer to coastlines where human impacts are greatest. According to the Project Seagrass, the new global map relied in part on ten years of crowdsourced observations and still revealed surprising pockets of loss and vulnerability.

How Communities and Science are Mapping Seagrass

On the western rim of the Indian Ocean, a new collaborative initiative called LaSMMI (Large-Scale Seagrass Mapping and Management Initiative) pulled together regional research institutes, universities and funders to make a field-verified map of seagrass across Kenya, Tanzania (including Zanzibar), Mozambique and Madagascar. The effort combines satellite imagery, local field surveys and capacity building so that coastal institutions can sustain monitoring themselves. “Seagrass meadows, often overlooked and underprotected, are vital to our planet,” said Dr Stacy Baez from Pew’s coastal wetlands campaign as the project launched. According to WIOMSA and partner briefings in 2025, LaSMMI follows the mapping success seen in Seychelles and aims to scale that approach across a whole region.

The Seychelles project is a good local case. There, research teams used high-resolution satellite basemaps and on-the-water photo quadrats to produce a national seagrass map and a first estimate of carbon stocks, work that directly supported Seychelles’ pledge to include blue carbon in its national greenhouse-gas inventory. Field teams described long days of snorkeling and diving to ground-truth images: Save Our Seas Foundation documented fieldwork where snorkelers and divers took photo quadrats and GPS points so scientists could train remote sensing models. Those on-the-water exercises turned community knowledge and local logistics into data that national planners could trust.

Citizen science tools are doing heavy lifting too. SeagrassSpotter — a global app and website run by Project Seagrass — makes it possible for divers, fishers, and beachgoers to upload photos with coordinates. Project Seagrass reports that SeagrassSpotter has gathered thousands of confirmed sightings from more than a hundred countries, and those community observations have been used to validate maps and identify areas that need field verification.

On the community-network side, Wales has built one of the most explicit national collaborations. Seagrass Network Cymru brings NGOs, scientists, government and volunteers together under a single platform and submitted a National Seagrass Action Plan to the Senedd. The Welsh Government has since awarded funding to develop that plan and support seed-collection and restoration trials, showing how a network can translate local action into funded national programmes. Carl Gough, the NSAP project manager, has written about bringing working groups and communities together to turn mapping into action. According to the Welsh Government statement, the funding helps the network move from plan to delivery.

These projects show different ways community action plugs into scientific methods. Typical workflows look like this: remote sensing imagery defines likely seagrass patches; local teams do ground-truthing with cameras and sediment cores; citizen scientists add photographic sightings and absence records; modelers combine the datasets to estimate habitat extent and carbon stocks; and finally managers use maps in spatial planning, fisheries rules or restoration priorities. The method blends low-cost community input with the rigor from universities and government labs.

From Maps to Action: Policy, Restoration and Practical Steps

Maps do not themselves stop damage, but they make targeted action possible. When countries can show where seagrass meadows are and how much carbon they contain, they can: include blue carbon in national inventories; target pollution and boat-anchoring regulations where meadows are dense; design restoration pilots in places with realistic chances of recovery; and build financial mechanisms (grants, blended finance, or carbon-related funding) to sustain long-term monitoring.

Policy follow-through is starting to appear. In Seychelles, the seagrass mapping work directly fed into national commitments on blue carbon; in Wales, government funding has begun to underwrite a national plan that includes community seed collection and trials. LaSMMI’s regional mapping is explicitly designed to give national agencies the data they need to strengthen coastal planning. These moves reflect a broader shift scientists and advocates have been arguing for: from ad-hoc conservation projects to integrated, evidence-based coastal management.

If you are a coastal manager, fisher, volunteer group or local councillor wondering what to do next, here are practical, evidence-based steps drawn from the projects above:

- Start with a simple map: use available satellite basemaps and citizen photos to build a draft map of likely seagrass locations. Community apps such as SeagrassSpotter make uploading evidence straightforward. According to Project Seagrass, crowdsourced sightings are an efficient first step to prioritize fieldwork.

- Ground-truth priorities: send small teams to take GPS-tagged photos and sediment samples in the most promising sites. Ground-truthing transforms a guess into a defensible data point for policy. Seychelles’ field teams combined snorkel photos with satellite data to produce national maps used for policy.

- Protect and regulate locally: where maps show dense meadows, draft simple bylaws to limit anchoring, dredging and pollution, and communicate the value of meadows to fishers. Local restrictions are far easier to enforce if they’re targeted by good mapping rather than blanket rules that lack support.

- Link mapping to funding: mapped carbon stocks and clear co-benefits (fisheries, tourism, coastal protection) help unlock national and international funding streams — from nature funds to climate finance. Documented blue-carbon estimates make a stronger case for money than vague descriptions. The Nature Communications study on global risk shows there is global economic value in preventing seagrass loss.

- Build community skills: invest in training for volunteers and local technicians so mapping and monitoring continue beyond the project lifetime. Wales’ National Seagrass Action Plan and LaSMMI both put capacity building at the heart of their work.

- Use phased restoration: where meadows are degraded but conditions allow recovery, start small, measure outcomes, then scale up. Trials — including seed collection and mechanical planting — have already been trialled in parts of the UK with community involvement. Scaling only after demonstrated success reduces waste and protects limited funding.

Voices from the field

Real people are already doing this work. In Seychelles, field teams described snorkeling transects and coordinating local boats and labs to collect imagery and samples — practical work that turned into national policy inputs. In Wales, volunteers collected more than a million seeds in a joint effort to test restoration approaches, and a project manager described the early months of organizing working groups and setting priorities. These are not abstract exercises: they are community knowledge, translated into scientific evidence and policy-ready maps.

Conclusion

Community seagrass networks and regional mapping initiatives are changing the conversation about blue carbon. They turn local observations into data that national governments and global scientists can use to estimate carbon, plan protection and design restoration. The message from recent projects is clear: invest in mapping, make the results public and use them to align coastal policy, fisheries management and climate plans. Protecting seagrass meadows is a practical, low-regret action that delivers climate mitigation, fisheries benefits and shoreline protection, but it depends on good maps, local engagement and sustained funding.

If you care about your coast, start by joining or encouraging a local seagrass-mapping effort, get a few volunteers trained in photo-quadrats or SeagrassSpotter uploads, and push for simple policies that protect mapped meadows from anchoring and pollution. Those small steps — photographed, geotagged and shared — are how communities turn a hidden blue carbon asset into a protected, valued part of the local and global climate solution.