Cradle-to-Grave Meaning in Environmental Sustainability

When people talk about a product’s environmental impact, they are often using the phrase “cradle to grave.” At its simplest, cradle-to-grave means tracking a product from the moment raw materials are extracted (the cradle), through manufacture, use, and finally disposal (the grave). It’s a practical, forensic way to answer big questions: how much carbon did this thing produce? How many toxins did it release? How much value was thrown away when it was discarded? The framework is not a slogan — it’s a measurement system used by governments, companies and scientists to make hard trade-offs visible. According to the ISO standards that define Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), cradle-to-grave studies must look at impacts across all stages of a product’s life and use standard methods so results can be compared.

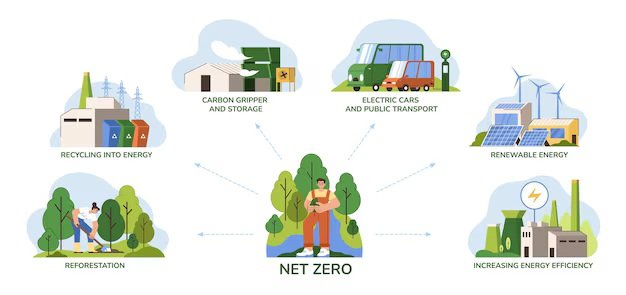

Cradle-to-grave is not the only approach — “cradle-to-cradle” and circular-economy thinking ask designers to imagine products as inputs for something new rather than waste. But even circular strategies depend on good cradle-to-grave measurement: you can’t fix what you don’t measure. The LCA process — which includes defining scope, compiling an inventory of flows, assessing impacts, and interpreting results — is the backbone that makes those choices evidence-based.

In This Article

- What “cradle-to-grave” actually measures

- Three Real-World Tests: E-waste, Plastics and Circular Business Models

- What Citizens, Companies and Policymakers Can Do

- Conclusion

What “cradle-to-grave” actually measures

A proper cradle-to-grave study counts everything the product consumes and discharges: fuels, materials, energy, emissions to air and water, land use, and sometimes social impacts. For example, life cycle work on plastics shows emissions from fossil feedstocks, processing, transport, use, and end-of-life — and it also exposes where a circular intervention (like better recycling) has the most leverage. But the professional literature also warns of a trap: different LCAs use different assumptions, so two seemingly similar studies can report very different results unless the methods are harmonised.

A recent study found inconsistencies in what plastics LCAs measure and how they’re done, so their results aren’t directly comparable; the review calls for clear, standardised methods so cradle-to-grave studies can reliably guide decisions.

Cradle-to-grave analysis doesn’t deliver a single moral verdict. Instead, it maps trade-offs: a lighter product might rely on more toxic chemicals during manufacture, while a repairable product might be heavier and use more metal but reduce lifetime impacts. That’s why honest cradle-to-grave reporting must disclose its assumptions, acknowledge data gaps, and highlight real uncertainties — otherwise it risks becoming greenwash rather than guidance.

Three Real-World Tests: E-waste, Plastics and Circular Business Models

Consider three different examples — a fast-growing waste stream, a material class that dominates public debate, and companies that try to do things differently.

1. Electronic waste

Global electronic waste (e-waste) is a textbook cradle-to-grave problem. Devices are small, complex, carry valuable metals and dangerous chemicals, and move through global supply chains that hide disposal impacts. According to the Global E-waste Monitor, the world generated a record 62 million tonnes of e-waste in 2022, and only a fraction is documented as safely collected and recycled; the problem is growing fast.

For people working with e-waste every day, those numbers are not just statistics—they are reality. Journalists and researchers who have spent time in Accra’s electronics clusters describe real lives caught between making a living and risking their health. Repairers and reclaimers told photographers and reporters how second-hand markets and salvaging provide livelihoods—yet open burning and informal dismantling make them sick. One photo essay follows Simon Aniah, who burns cable insulation to recover copper; his story is not a parable but a real choice between earning an income and facing long-term health harm. Projects that attempt to “formalise” these livelihoods encounter the same tension: ending hazardous practices without replacing income only shifts the harm elsewhere.

2. Plastics

Plastics often appear in cradle-to-grave studies because their life cycle links fossil extraction, manufacturing, use, leakage into the environment, and usually poor end-of-life outcomes. Reviews of plastics’ life cycle impacts highlight two key points: first, cradle-to-grave measurement reveals unexpected hotspots (for some products, manufacturing dominates the footprint; for others, disposal and leakage are the biggest problems); second, the policy response is crucial. For example, rethinking polymer design or investing in high-quality recycling infrastructure can lower overall impacts — but demonstrating that benefit requires LCAs that account for substitution effects and realistic recycling yields.

Recent scientific reviews call for stronger, harmonised LCA methods so that policy decisions (such as bans, taxes, or incentives for recycled content) actually reduce harm rather than simply shift it.

3. Businesses that close loops

Some companies have translated cradle-to-grave thinking into concrete business models. Interface, a global carpet maker, began a take-back program called ReEntry decades ago to reclaim used carpet tiles for reuse and recycling; the company reports millions of square yards diverted from landfill and tens of millions of pounds of material reclaimed — a practical example of redesigning the grave into a cradle. Similarly, Patagonia’s Worn Wear programme repairs and resells garments to extend their useful life. These programs don’t eliminate cradle-to-grave questions (transport for returns, energy for recycling, and material downcycling still matter), but they show how measurement, business incentives, and design can reduce lifetime impacts when combined.

What Citizens, Companies and Policymakers Can Do

Cradle-to-grave is not just academic; it should change behaviour. For citizens, the clearest actions are to buy less, pick products designed for repair, and support brands that publish transparent life-cycle data. For example, choosing clothing with repair programmes or companies that publish LCAs helps reward longer life and lower lifetime impacts. For repairers and informal workers, the path is harder and needs policy support: formalisation, access to safer tools, training, and guaranteed markets for reclaimed materials — otherwise well-intentioned bans or site clearance simply erase incomes without improving environmental outcomes.

Companies must do two things well. First, measure honestly: publish cradle-to-grave LCAs that show what was assumed and where data are thin. Second, act on the results: redesign products to reduce impact in the stages the LCA identifies as worst, and invest in infrastructure (recycling, repair networks) to make circular claims real. The examples of Interface and Patagonia show that business models — leasing, take-back, repair services — can turn part of the grave into a new cradle, but these models need scale and good measurement to avoid unintended trade-offs.

Policymakers carry the heaviest lifting. Standardising LCA rules (so studies are comparable), requiring extended producer responsibility (so companies pay for end-of-life management), and investing in public recycling and repair infrastructure will shift markets. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation and other thought leaders argue that a combination of rules, procurement practices and incentives can move entire sectors toward circularity — but it must be built on consistent cradle-to-grave evidence so policies target real harms, not convenient narratives. As the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s leaders have repeatedly noted, system change requires design, business leadership and policy to align.

Practical Checklist for Anyone Who Wants to Apply Cradle-to-Grave Thinking

Demand transparent LCAs, ask how a company deals with end-of-life, prioritise repairable and reusable goods, and push for policies that make producers responsible for disposal. For public officials, require standardised life-cycle reporting in procurement, and invest in safe jobs for people who currently work in hazardous, informal recycling. These are not small asks; they are the practical steps that move a measurement framework into safer workplaces, fewer emissions and products that stop being a problem the moment they are thrown away.

Conclusion

Cradle-to-grave is a simple phrase with a complicated truth. It forces us to track consequences across time and place. When measured honestly and used to redesign systems, it becomes an engine for better choices — for people who make things, those who use them, and the communities that pick up the pieces. If we want a world where fewer things end in a toxic grave, the cradle-to-grave map will get us there — but only if we read it, share it, and act on what it shows. ISOITURSC Publishing