Is Water a Renewable Resource?

When we turn on the tap, water flows out effortlessly. It’s easy to assume there’s an endless supply, but is that really true? While the Earth has a natural water cycle that recycles and replenishes water, human actions—like pollution, overuse, and climate change—are disrupting this balance. In some places, water sources are drying up faster than they can be replenished, making it clear that water isn’t as limitless as we once thought.

Take the Aral Sea, for example. Decades of unchecked irrigation nearly wiped it off the map. In 2018, Cape Town, South Africa, faced “Day Zero,” a crisis where water reserves were nearly depleted, forcing strict rationing. These are stark reminders that water, despite its renewability in theory, can become scarce if mismanaged.

In this guide, I will help you understand the science behind water’s renewability, explore real-world examples of water crises, and hear from experts on what we can do to protect this vital resource. Understanding the reality of water’s availability isn’t just for scientists and policymakers—it affects us all. Let’s explore whether water is truly renewable and, more importantly, how we can ensure there’s enough for future generations.

In This Article

- Understanding Water’s Renewability

- When Water Becomes Non-Renewable

- Case Studies: The Reality of Water Scarcity

- The Role of Groundwater: A Hidden Crisis

- Solutions for Sustainable Water Management

Understanding Water’s Renewability

The Water Cycle: Nature’s Recycling System

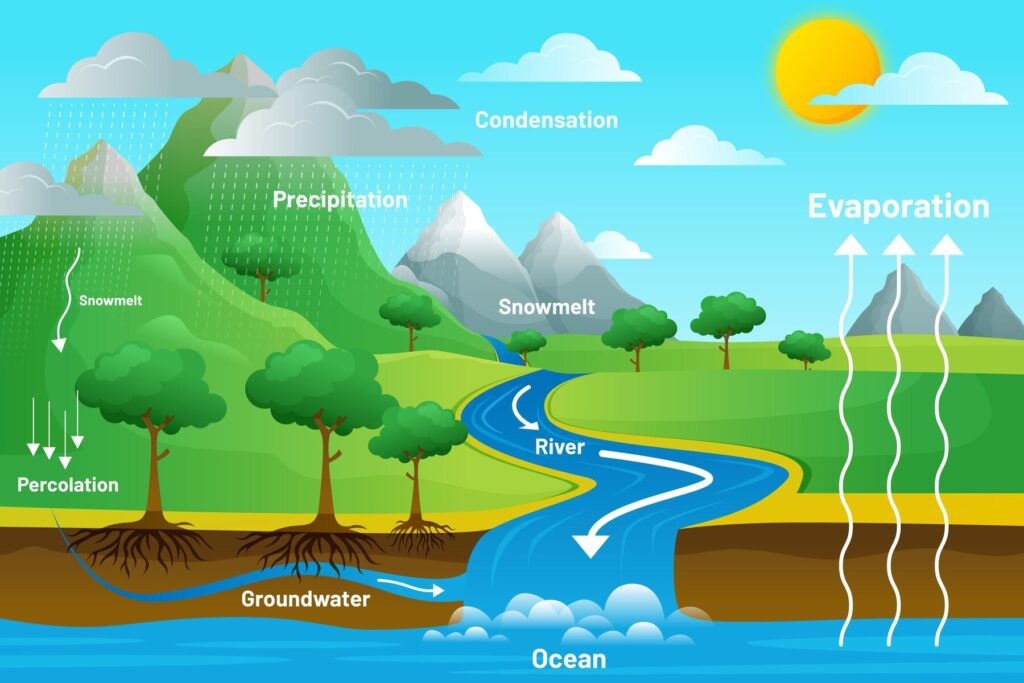

Water is traditionally considered a renewable resource because of the hydrological cycle. This natural system moves water around the planet, keeping it in circulation. Here’s how it works:

- Evaporation: Heat from the sun causes water from oceans, lakes, and rivers to rise into the atmosphere as vapour.

- Condensation: The vapour cools and forms clouds.

- Precipitation: When clouds become heavy, water falls back to Earth as rain, snow, or hail.

- Collection: This water gathers in lakes, rivers, and underground reservoirs, ready to restart the cycle.

At first glance, this process seems endless. Water evaporates, falls back to Earth, and the cycle repeats. But here’s the catch: human activity is disrupting this natural balance, making water availability a growing global concern.

When Water Becomes Non-Renewable

1. Over-Extraction: Using Water Faster Than It Replenishes

Many parts of the world depend on underground water reserves (aquifers) for drinking water and agriculture. These aquifers take hundreds, sometimes thousands, of years to recharge. But we are pumping water out far faster than nature can put it back. For example, the Ogallala Aquifer in the U.S., which supplies water to millions, is being depleted at an alarming rate. If this continues, future generations may have little or no water left in these reserves.

2. Pollution: Destroying Our Freshwater Sources

Freshwater lakes and rivers should, in theory, keep replenishing themselves. However, pollution from factories, farms, and cities is making water unsafe to drink or use. In some places, pollution has reached such severe levels that water sources are no longer viable for human consumption. Cleaning up contaminated water can take decades, making it functionally non-renewable.

3. Climate Change: Disrupting the Natural Flow of Water

Climate change is altering rainfall patterns, causing longer droughts in some areas and severe flooding in others. Countries that once had stable water supplies are now struggling with scarcity. The unpredictability of weather patterns makes it harder for communities to plan and manage their water resources efficiently.

Case Studies: The Reality of Water Scarcity

Case Study 1: The Disappearance of the Aral Sea

The Aral Sea, once one of the world’s largest lakes, has almost vanished. In the 1960s, Soviet irrigation projects diverted the rivers that fed the lake to support massive cotton farming operations. At the time, no one thought much about long-term consequences. But over the decades, as the water was drained for agriculture, the sea shrank at an alarming rate.

According to research by Micklin (2007), the Aral Sea has lost more than 90% of its volume since those irrigation projects began. What’s left is a desert filled with toxic dust from the exposed lakebed, which has poisoned local communities and devastated fisheries that once thrived in the area. The disappearance of the sea has destroyed livelihoods, increased respiratory diseases due to airborne pollutants, and even altered local weather patterns, making winters colder and summers hotter.

This case is a reminder that water, while renewable in theory, can be permanently lost if overused and mismanaged.

Case Study 2: Cape Town’s “Day Zero” Crisis

In 2018, Cape Town, South Africa, faced an unprecedented crisis. A prolonged drought, combined with population growth and inefficient water use, brought the city dangerously close to running out of water. Officials warned of a “Day Zero”—the day when taps would run dry.

To prevent a complete disaster, drastic conservation measures were put in place. The government limited residents to just 50 litres (13 gallons) of water per person per day—for drinking, cooking, bathing, and all other needs. Compare that to the average American, who uses about 300 litres (79 gallons) per day without thinking twice.

| City | Year | Population | Daily Water Allowance per Person (Liters) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cape Town | 2018 | 4.6 million | 50 |

| New York | 2023 | 8.5 million | 300 |

| Mumbai | 2023 | 20.4 million | 135 |

The situation was so dire that people had to take two-minute showers, reuse laundry water, and let their gardens die. Businesses installed water-saving devices, and farmers had to change how they irrigated crops.

Cape Town managed to avoid running out of water by implementing extreme conservation efforts and investing in desalination and groundwater projects. However, the crisis was a wake-up call for cities worldwide: water isn’t unlimited, and it’s tough to get back once it’s gone.

Learn More: How Can Groundwater Depletion Affect Streams and Water Quality?

The Role of Groundwater: A Hidden Crisis

Groundwater, the water stored beneath the Earth’s surface, is a vital resource that supplies drinking water to billions and supports agricultural and industrial activities. However, its depletion has become a pressing global concern. The United Nations reports that 21 of the world’s largest aquifers are being depleted faster than they can recharge.

| Major Aquifer | Location | Depletion Rate (Annual) |

|---|---|---|

| Ogallala Aquifer | USA | 12 billion cubic meters |

| North China Plain | China | 22 billion cubic meters |

| Arabian Aquifer | Middle East | 16 billion cubic meters |

Personal Accounts Highlighting the Crisis

In the San Joaquin Valley of California, artist and educator Kristine Diekman embarked on the “Run Dry” project to capture the human side of water scarcity. Through short documentary films, personal narratives, and photographs, she sheds light on communities struggling without reliable access to clean water. Diekman’s work emphasises that water is indispensable for empowerment, health, dignity, and economic security. Her project delves into how race, class, migration, water policy, climate, hydrology, and agricultural history have intertwined to create the current water crisis in the region.

Similarly, anthropologist Lucas Bessire’s book “Running Out: In Search of Water on the High Plains” offers a personal narrative intertwined with analytical insights into the depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer. Stretching from South Dakota to Texas, this aquifer supports a significant portion of the world’s grain production but is rapidly being drained. Bessire’s work explores the politics and livelihoods that have sustained this extraction, drawing from his family’s multi-generational ties to Kansas farming. His narrative underscores the paradox where the escalating dependency on the aquifer contributes to its undoing, reflecting a broader global challenge.

Regional Impacts and Responses

The consequences of groundwater depletion are evident across various regions:

- Iran: Extensive groundwater extraction has led to significant land subsidence, with satellite images revealing areas sinking by over 10 cm annually. This has resulted in infrastructure damage, including impacts on airports and roads, highlighting the urgent need for coherent groundwater policies.

- Spain: In Valencia, catastrophic floods have compounded existing water scarcity issues. Contaminated local water sources have forced residents to rely on bottled water, raising concerns about the sustainability and equity of water distribution, especially when private companies profit from extracting water in already stressed regions.

- Arizona, USA: The state’s Department of Water Resources designated an “active management area” for the Willcox Groundwater Basin to regulate use and prevent rapid depletion due to agricultural activities. This move aims to preserve groundwater supplies for future generations, addressing concerns about drying wells and land fissures.

- Vanuatu: Rising sea levels and violent cyclones have led to saltwater intrusion into groundwater sources, contaminating the water supply of low-lying islands. This has made wells undrinkable, forcing communities to rely on rainwater or relocate, underscoring the vulnerability of island nations to groundwater challenges.

- Australia: In regions like South Australia’s south-east and south-west Victoria, nearly 200 years of agricultural and domestic use have led to groundwater decline. This threatens natural ecosystems and the region’s economy, with experts warning of a potential ecological disaster if current practices continue.

Learn More: Sustainable Water Management Practices

Solutions for Sustainable Water Management

1. Improving Water Conservation Efforts

Governments need to step up. In places where water is scarce, they should enforce smart rationing plans, invest in infrastructure, and stop leaks in supply systems.

At home, we can do our part too. A dripping faucet might not seem like a big deal, but those drops add up—thousands of litres wasted every year. Fixing leaks, using water-efficient appliances, and turning off taps when brushing our teeth are small but powerful steps.

2. Restoring Natural Water Cycles

Nature knows how to take care of itself—if we let it. Planting trees helps groundwater recharge, preventing droughts. Restoring wetlands acts like a natural filter, cleaning water before it reaches our rivers and reservoirs. If we protect these systems, they will protect us.

3. Investing in Water Recycling and Desalination

Some countries are already leading the way. Singapore recycles wastewater into clean drinking water, while Israel reuses nearly 90% of its wastewater. Desalination, which turns seawater into freshwater, is another solution. But it’s expensive and energy-heavy, so we must use it wisely.

A Call to Action

Water is renewable—but only if we treat it with care. Let’s take action now:

- Cut back on daily water use.

- Support policies that promote sustainability.

- Teach others about the importance of conservation.

Water is precious. Let’s not waste it.